Credit: Armas via Suaq Project

For many thousands of years, humans have used medicinal plants to help heal wounds. It turns out, some of our primate relatives may have, too.

In Indonesia, scientists observed a large male orangutan with an open wound on his face.

To their surprise, he sought out a special plant called akar kuning that orangutans usually do not eat. He consumed a large quantity of leaves, then chewed more into a paste, applied it to the wound and left it there.

Within five days, the wound had closed. Within six weeks it was gone, with hardly a scar.

Local folk healers have long recognized that akar kuning has medicinal properties. Modern chemical analysis has found it contains antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antifungal and antioxidant compounds.

Somehow the orangutan knew this too. And he’s not alone. Orangutans in Borneo have been known to rub other types of chewed leaves on their arms, perhaps to relieve sore muscles.

Surprisingly, there are many examples of animals self-medicating with plants. Dogs eat grass and chimps eat bitter herbs to soothe their stomachs. Canada geese eat whole leaves to expel tapeworms. Some rats line their nests with aromatic plants, likely to fumigate parasites.

Ancient Greeks, Egyptians and Arabs studied animals’ medicinal use of plants to inform their own. What more might we learn today from animals’ plant choices in the wild?

Background

Synopsis: In a surprising first in June of 2022, researchers observed Rakus, a male Sumatran orangutan, tend to a deep wound on his face, which closed in five days and completely healed with a barely noticeable scar in less than six weeks.

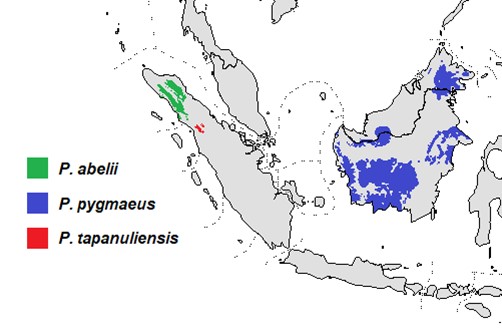

- Orangutans are critically endangered primates that live in the tropical rainforests of Borneo and Sumatra in the Indonesian Archipelago.

Present-day range of the three critically endangered orangutan species in the Indonesian Archipelago: the Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelii) in green, the Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) in blue and a species identified in 2017, the Tapanuli orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis) in red.

Credit: Mariomassone (talk) 11:36, 21 June 2020 (UTC), public domain, via Wikimedia Commons- Orangutans (genus Pongo) diverged from the other great apes (humans, gorillas, chimps and bonobos) more than 14 million years ago (ED-135 Last Branch on the Family Tree).

- During the Pleistocene Epoch, orangutan species ranged from Southeast Asia to South China.

- Orangutans have long arms and short legs and spend most of their time in trees.

- Covered with red-brown hair, males are about twice the size of females at 165 lb (75 kg).

- They eat fruit, vegetation, bark, honey, insects and bird eggs. They will only eat meat as a fallback nutritional source if vegetation is not available.

- They live for over 50 years in the wild and in captivity.

- Dominant males develop distinctive cheek pads called flanges and make long calls to attract mates and intimidate rivals.

- Most orangutans are solitary. Social bonds only occur between mothers and their dependent offspring.

- Researchers commonly observe primates in their wild habitats, and critically endangered orangutans are no exception.

- In 2009, a research team in Indonesia observed the arrival of a young Sumatran orangutan to the Suaq Balimbing area of the Gunung Leuser National Park in South Aceh. It is the only site where Sumatran orangutans are being monitored in a peat swamp forest setting.

- He didn’t have the flanged cheek pads of a mature male at that time, so he was thought to be about 20 years old.

- After he ate every flower off of a gardenia bush in one sitting, the research team named him Rakus, which means “greedy” in Indonesian.

- In 2021 Rakus had a growth spurt and developed the flanges of a mature male, and soon afterward, he began fighting with other males for dominance.

- He sustained a facial wound, possibly caused by the canine tooth of a rival, which was first observed below his right eye on June 22, 2022.

- Three days later, on June 25, he ripped leaves off a liana plant. First he ate leaves for nearly 15 minutes, then he chewed more leaves for several minutes, applying the juice to the wound several times. Then he covered the open wound with a poultice (herbal bandage) of the chewed leaves and left it there.

- Orangutans typically do not eat liana, but Rakus consumed more leaves the next day and rested nearby for a few days.

Around a month after applying medicine to his wound, Rakus has fully healed, with only a slightly noticeable scar. This photo was taken in August 2022, roughly six weeks after the injury was first spotted.

Credit: Safruddin via Suaq Project - Rakus’s facial wound closed in just a few days, by June 30, without infection.

- By August 5, six weeks later, the wound had healed, leaving a barely noticeable scar. Two years later, he is still going strong.

- This was the first scientific record of intentional self-treatment of an injury by a wild animal using a plant with known medicinal properties.

- Liana, or yellow root, is a climbing vine native to Southeast Asian tropical forests known for its medicinal properties as a pain-relieving analgesic, fever-reducing antipyretic and fluid-reducing diuretic.

- It is known locally as akar kuning and its Latin name is Fibraurea tinctoria.

Photo of Fibraurea tinctoria, the medicinal herb that Rakus applied to his wound.

Credit: Cheongweei Gan, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons - It is used by local indigenous healers to treat malaria, diabetes and dysentery.

- These leaves have been shown to contain chemical compounds with antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antifungal and antioxidant properties.

- It is known locally as akar kuning and its Latin name is Fibraurea tinctoria.

- While evidence of hominid use of medicinal, poisonous and psychoactive plants extends well into the Pleistocene Epoch, the progression of self-medicating behavior in animals is obviously much more difficult to assess.

- Since the time of Aristotle and Pliny the Elder, there have been accounts of zoopharmacognosy–“animal medicine knowledge.”

- Egyptians traced much of their medical knowledge to observing the wisdom of animals.

- Animals may use plants to maintain health.

- Bears emerging from hibernation seek out nutritious wild garlic.

- They may also consume plants to treat wounds or illness, neutralize toxins and repel parasites.

- Chimps chew on bitter plants and rough leaves to sooth their stomachs.

- Dogs eat grass which may be helpful for purging stomachs and deworming.

- Some rats line their nests with aromatic plants to fumigate parasites.

- Canada geese swallow whole leaves to expel tapeworms.

- Hunters learned from wild stags wounded by arrows that dittany, wild oregano, has antiseptic, anti-inflammatory and coagulating effects to help healing.

- Topical application of pharmacological substances is far rarer:

- In the fourteenth century, an Arabic manuscript notes that wild goats chew and apply sphagnum moss to their wounds, which combats infection by neutralizing bacteria.

- Bornean orangutans have been observed macerating leaves and rubbing the mush on their appendages, possibly to treat sore muscles.

- Wild chimps in Gabon have been seen rubbing insects around their wounds—is it some sort of treatment?

- Did humans and animals learn about natural medicines by observing each other?

- How did a solitary animal like Rakus know how to heal his wound in such an expert way?