Credit: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

For millennia, people have been drawn to volcanoes.

Why? Because before they arrived, the volcanoes had erupted.

Their lava, ash and debris covered the surrounding area, making for fertile farmlands that drew settlers … who may not have recognized that the volcanoes could erupt again.

And that’s just what happened around Italy’s Mount Vesuvius. Long before the Romans, people had come to farm there. When Rome eventually controlled the region, inspired by the pleasant climate and bountiful agriculture, they named it Campania Felix—the happy, fertile countryside.

One of the happiest towns was Pompeii, a popular vacation spot of the day. But Mount Vesuvius would change all that.

In AD 62, it sent earthquakes through the region, displacing residents. Most had returned when, 17 years later, Vesuvius erupted.

First, it blasted a spire of ash and pumice 10 miles into the sky. This rained down on Pompeii, leaving a layer 8 feet thick. Most citizens fled, but 2,000 remained, sheltering in stone houses and cellars.

The next day, clouds of burning hot toxic gas flowed down the mountain, instantly suffocating residents. More ash rained down, encasing the victims in their final positions.

Their tragic end, however, would be a great boon to historians centuries later – which we’ll discuss in the next EarthDate.

Background

Synopsis: More than 19 centuries ago, on August 24, AD 79, Pliny the Younger recorded the massive eruption of Mount Vesuvius, just 14 mi (22.5 km) from ancient Naples. It changed the region forever.

- Located along the convergence zone between tectonic plates that collided during the Alpine orogeny, Italy is the only country in Europe that has active volcanoes on the mainland.

- Smaller microplates that jostle for space in this dynamic system have contributed to the development of several volcanic centers along Italy’s western coast at various times.

- In a recent EarthDate episode (ED-364 Life in the Fiery Fields) we talked about a modern-day volcanic threat in the western suburbs of the city of Naples that lie within the Campi Flegrei caldera.

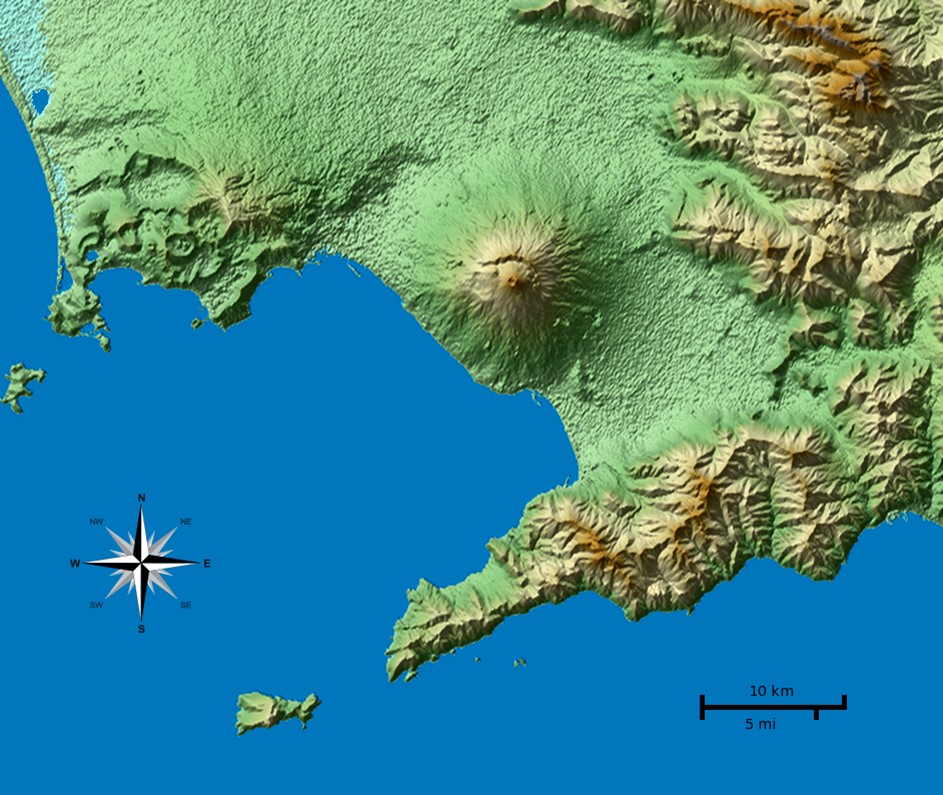

- In the western Italian region of Campania, the Campanian volcanic arc includes several calderas, including the Campi Flegrei caldera to the west of Naples, and the Somma caldera to the east of Naples.

This shaded terrain map of Napoli Bay shows the collapsed caldera of the Campi Flegrei to the west of the city of Naples and the prominent peak of Mount Vesuvius crowning the Somma caldera to the east.

Credit: Morn the Gorn, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons- Volcanic calderas that contain a newer central volcanic cone are known as “sommian” calderas after the Somma caldera, which contains the younger, more famous Mount Vesuvius volcano.

- Ruins of the ancient towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum confirm the destructive capability of Mount Vesuvius, which began forming 17,000 years ago.

- Eight major eruptions have occurred since then, including the devastating pyroclastic flows of the August 24, AD 79, eruption, with an ejecta volume of 1 mi3 (4.4 km3) and a volcanic explosivity index of 5 (VEI-5), that destroyed Pompeii and Herculaneum.

Mount Vesuvius erupting in March 1944 as photographed from a U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF) B-24 during the Second World War. Nearby Pompeii Airfield was closed after the eruption, when more than 70 B-25 bombers belonging to the U.S. Army 12th Air Force were destroyed.

Credit: John Reinhardt, USAAF B-24 tail gunner, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons - Smaller eruptions occurred from 1631 through 1944, and the iconic Mount Vesuvius has been fairly quiet since then.

- Today, Campania is the most densely populated province of Italy. Why would so many Italians choose to live in the shadow of a deadly volcano?

- Rich black volcanic soils made the region an agricultural breadbasket for Italy, attracting settlement for millennia.

- Before 700 BC, the region was inhabited by the Osci, followed by Etruscans then ancient Greeks living in agricultural villages.

- When the Samnites attempted to invade the region in the fourth century BC, residents called upon the Romans from southern Italy to protect them.

- By 200 BC, Campania had become part of the Roman Empire. Latin was adopted as its official language except in Greek-speaking ancient Naples (Neápolis), which was a center of early Greco-Roman culture.

- With its incredible natural beauty, the rich agricultural region became known as Campania Felix, Latin for “happy, fertile countryside.”

- Campanian towns like Pompeii and Herculaneum were popular holiday resorts for the citizens of Rome, which was about 150 mi (240 km) away.

- Roman emperors Claudius and Tiberius both chose Campania as a holiday destination, and Nero had a holiday villa in the western suburbs of Pompeii.

- Just 5 mi (8 km) southeast of the crest of Mount Vesuvius and overlooking the Sarno River, Pompeii was a bustling commercial center along the only route linking the Bay of Naples coastline to the fertile inland agricultural region.

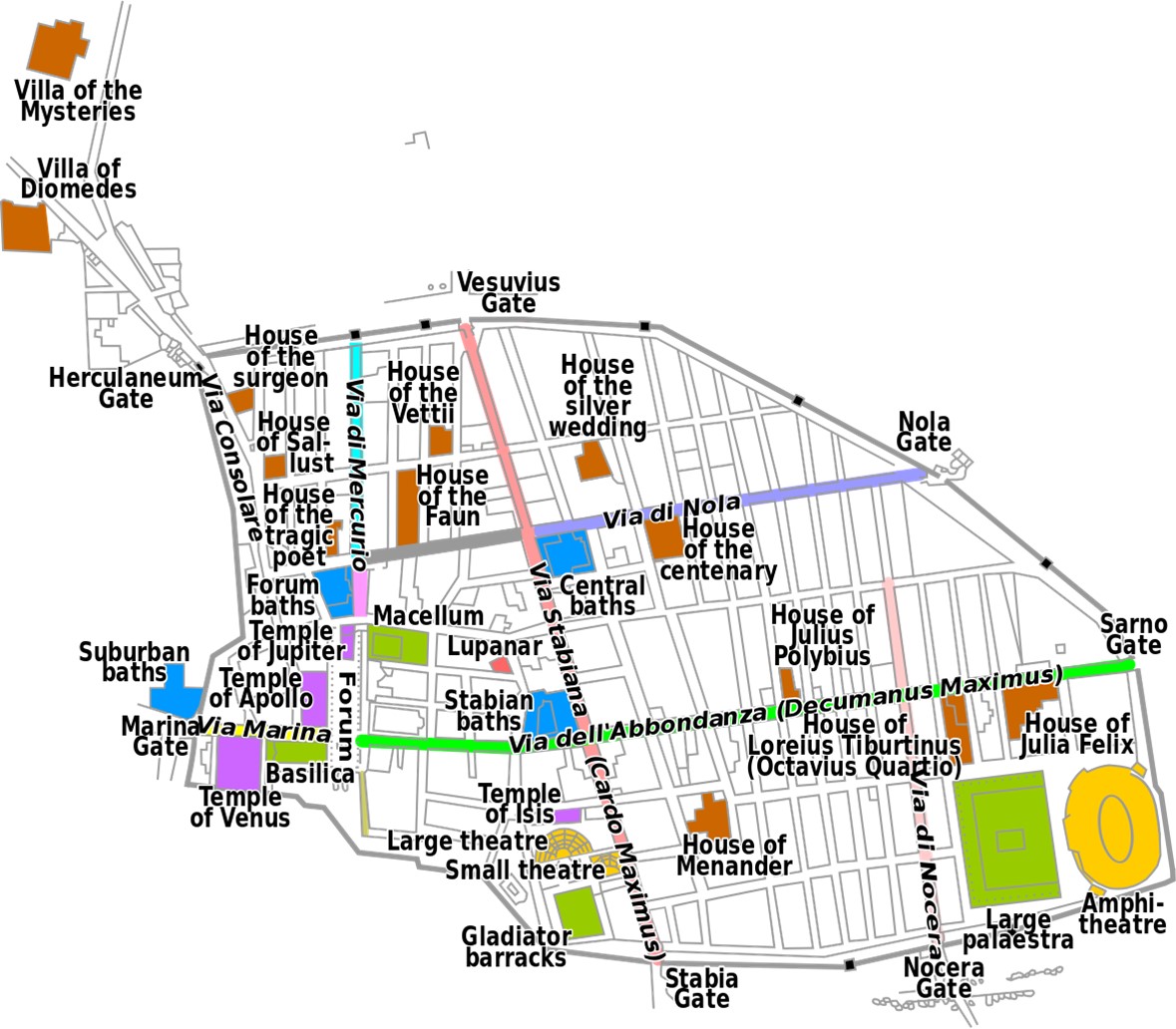

A street map of ancient Pompeii. The city was covered in 14 to 17 m of volcanic ash and frozen in time in AD 79.

Credit: cmglee, MaxViol, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons - Pompeii had 11,000 to 12,000 citizens that enjoyed a complex water delivery system, long avenues, a forum, an amphitheater that seated 20,000, a gymnasium, 2 theaters, hotels and more than 200 cafés and bars.

The excavated ancient city of Pompeii as seen from above using a drone, with Mount Vesuvius in the background. At 150 acres, it is one of the world’s largest archaeological sites.

Credit: ElfQrin, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Pompeii’s prosperity ended suddenly in AD 79 when Mount Vesuvius erupted violently, entombing thousands of citizens frozen in time on this fateful day.

- Seventeen years earlier, in AD 62, earthquakes rumbled through Pompeii, destroying infrastructure that was still undergoing repair 17 years later. Some of its luckier citizens were displaced to the countryside after this event and never moved back.

- With this recent history, when earthquakes racked the ground in August of 79, it wasn’t an immediate cause for alarm, and many people kept at their work.

- Around midday on August 24, after centuries of dormancy, Mount Vesuvius erupted, shooting ash and pumice upward as much as 10 or 12 mi (16–19 km) into Earth’s stratosphere.&

- Seventeen-year-old Pliny the Younger witnessed the eruption from the coast near Naples.

- He described it in a letter as follows: “I cannot give you a more exact description than by likening it to that of a pine-tree, for it shot up to a great height in the form of a very tall trunk, which spread itself out at the top into a sort of branches.”

- The letter describes the death of his famous naturalist uncle, Pliny the Elder, an admiral of the Roman fleet, while trying to evacuate citizens of coastal towns during the eruption of August 24, 79. The translation of his entire letter can be found here.

- While Pliny’s letter clearly dates his observation of the eruption “On the 24th of August, about one in the afternoon,” the excavation of Pompeii has revealed many room-warming braziers filled with charcoal, plentiful autumn fruits and nuts in the markets and graffiti in charcoal (that would tend to wear away within a couple months) dated October 17. So, the exact date of the eruption is disputed, and may have been as late as October or November of 79.

- Today, Plinian eruptions are defined as violent large-volume eruptions that produce quickly expanding clouds of gas, rock and ash, such as the 1980 Mount St. Helens, 1990 Pinatubo and 2022 Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai eruptions.

- After the initial explosive eruption, ash and pumice stones up to 3 inches in diameter rained down like hail for 12 hours, covering Pompeii in about 8 ft (2.5 m) of pumice. The first layer was white, while the second layer was gray. Some roofs collapsed under the weight of these layers, killing some citizens. Many fled during this stage of the eruption.

- Most of the two thousand people who stayed in Pompeii hoping to ride out the eruption in stone structures and cellars were found on top of these layers of pumice, indicating they survived the initial ashfall episode.

- But the next morning, a series of six pyroclastic clouds of searing hot 550° F (300° C) toxic gases surged down the mountainside at up to 70 mph (110 km/h), with the fourth wave of these surges barely reaching Pompeii, instantly killing the remaining residents, then encasing them in ash.

- Ash rained down for a total of two and one-half days, covering 200 mi2 (500 km2) of western Italy, burying Pompeii in more than 13 ft (4 m) of pumice, ash and debris.

A map showing the cities and towns affected by ash from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. The general shape of the ash and cinder fall is shown by the dark area to the southeast of Mount Vesuvius.

Credit: MapMaster, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons - Unusual northwesterly winds resulted in Pompeii being completely covered by the ash cloud. On a more typical summer day, prevailing southwesterly winds might have blown most of the ash farther inland.

- The coastal resort town of Herculaneum, on the western flank of Vesuvius, saw more intense pyroclastic flows; citizens sheltering there were incinerated, so that only bones were left. The town was buried in 65 ft (20 m) of volcanic debris.

- After the eruption, the Roman Emperor Titus, who ruled from AD 79 to 81, provided financial support for relocation of displaced residents and funded building restoration projects throughout Campania, especially for temples.

- Aside from Pliny’s letter, the Campanian villages buried in the eruption were forgotten for 1,500 years.